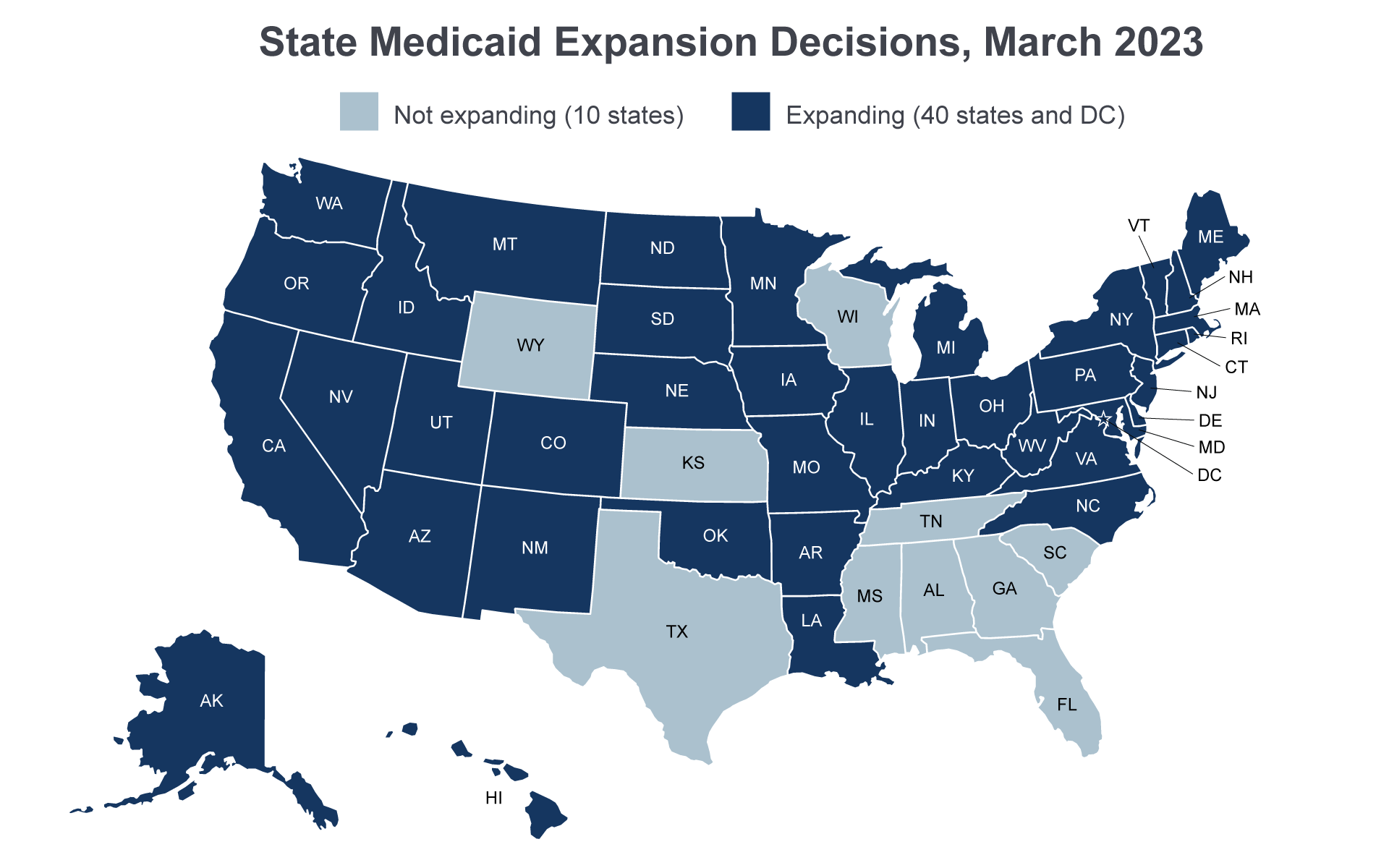

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, P.L. 111-148, as amended) extended Medicaid eligibility to all adults under age 65 (including parents and adults without dependent children) with incomes below 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). However, the June 2012 Supreme Court ruling in National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) v. Sebelius effectively made the expansion an option for states. As of March 2023, 40 states and the District of Columbia have chosen to adopt the adult expansion. The ACA provided the territories with additional funds for their Medicaid programs, but gave them the option of expanding Medicaid.

For more on the effect of the Medicaid expansion, see Medicaid enrollment changes following the ACA and Changes in coverage and access.

Notes: Some states use Section 1115 research and demonstration waivers to test policies not allowed under traditional Medicaid, such as imposing higher cost sharing for some expansion enrollees or placing limitations on certain mandatory benefits.

Sources: Medicaid State Plan Amendments, Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waiver documents, and media accounts.

Alternative policies for Medicaid expansion populations

Some states use Section 1115 research and demonstration waivers to test policies not allowed under traditional Medicaid, such as imposing higher cost sharing for some expansion enrollees or placing limitations on certain mandatory benefits.

Specifically, most of the states with these types of demonstrations have implemented beneficiary contributions programs, which involve changes to the premium and cost sharing schedules. Several states restrict retroactive eligibility. A small number of states place limitations on the non-emergency medical transportation benefit. One state, Arkansas, is using premium assistance to purchase plans on the exchange under its demonstration. Although several states planned to implement work and community engagement requirements, such requirements are not currently in effect in any state.

In 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) notified many of these states that certain elements of their demonstrations (i.e., work and community engagement requirements) were being withdrawn, and that other elements of their demonstrations would be reviewed.

Eligibility determinations

Under the ACA, Medicaid eligibility for most enrollees is determined using Internal Revenue Service definitions of modified adjusted gross income (MAGI). The goal of these new income counting rules is to coordinate Medicaid determinations with eligibility determinations for the subsidies for coverage available through health insurance exchanges. Prior to the ACA, states could use their own income disregards when determining eligibility for Medicaid. However, with the move to MAGI, states are no longer able to use state-specific disregards, deductions, or assets when determining Medicaid eligibility. The ACA also set a single income eligibility disregard equal to 5 percentage points of the FPL. For this reason, eligibility is often referred to at its effective level of 138 percent FPL, even though the federal statute specifies 133 percent FPL. The MAGI methodology is used for the new adult group as well as for children, pregnant women, and parents. Eligibility for those who are over age 65 and eligible on the basis of a disability or a need for long-term services and supports continues to be determined through pre-ACA methods.

Individuals also must be able to apply for Medicaid and subsidized coverage on the exchanges through a single application, and states must be able to share eligibility information with their state or federal exchanges. Additionally, state Medicaid agencies must rely on electronic data sources to the greatest extent possible to verify eligibility and to conduct administrative renewals. These changes, along with the move to MAGI-based eligibility, required states to upgrade their existing eligibility and enrollment systems. In late 2013 and into 2014, a number of states experienced early coordination problems between Medicaid and the exchanges and with the new systems, and developed mitigation strategies with CMS to address them; in some states, these issues resulted in gaps or duplication in coverage (GAO 2015). Many of these initial technical issues have since been resolved (Brooks et al. 2020).

Benefits

Individuals enrolled as part of the new adult group receive an alternative benefit plan (ABP), which is a benchmark plan modeled on commercial insurance coverage, rather than the traditional Medicaid benefit plan. Individuals with special medical needs are exempt from the ABP and states have flexibility to include additional benefits. In addition, these benefit packages must cover the 10 essential health benefits specified in the ACA. Essential health benefits are defined as ambulatory services, emergency services, hospitalization, maternity and newborn care, mental health and substance abuse services, prescription drugs, rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices, laboratory services, preventive and wellness services, chronic disease management, and pediatric services, including oral and vision care. While states are allowed to offer ABPs to the new adult group that are less comprehensive than benefits offered to other Medicaid beneficiaries, most states have chosen to align their ABPs with traditional Medicaid benefits (CRS 2018).

The ACA also required the federal government to pay 100 percent of state Medicaid costs for certain newly eligible individuals through 2016; at that point the matching rate began phasing down to 90 percent in 2020 and thereafter. The term newly eligible applies to individuals who would not have been eligible for Medicaid in the state as of December 1, 2009, or who were eligible under a waiver but not enrolled because of limits or caps on waiver enrollment. In states that expanded eligibility to low-income parents and adults without children prior to the ACA, the traditional matching rate was increased gradually until it equaled the newly eligible matching rate in 2020. For more information, see state and federal spending under the ACA.